Go South Young Man

I worked in the field of international development for many years, and more than a few people in Canada would say things like ‘I’ve always wanted to help build a school in Africa.’ They know how to build schools in Africa, I’d reply, I hope with some grace toward their good-heartedness.

I’d sometimes add that global poverty is a complex stew of history, exploitation, culture, racism, trade, geography and luck. Development or international solidarity or however you want to define it, can get messy. It can fail. It can even work.

But, of course, I’m being a hypocrite (and yet another person not from the Southern World talking about development in the Southern World). That’s because in 1986, at the age of 21, I volunteered abroad to help build – not physically, but pedagogically – a school in the Caribbean. In this case a preschool, in the rural community of Barrouallie in the country of St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

The main Vincentian island and a trailing of smaller islands that make up that nation break the ocean’s surface in the southern portion of the Windward Islands, above Grenada which is above Trinidad & Tobago, which in turn is above Venezuela, South America. At the time, St. Vincent was considered by many to be the second poorest (economic) country in the Caribbean after Haiti (it no longer is).

Even back then, for all my earnest desire to do something good in this world – because of an inchoate colonial guilt of being from the ‘First World’ or because like many of us I was looking for some bigger purpose in my life, and as a non-believer that would have to come from within – I knew it was me who would get the most out of this.

I worked with wonderful people – Vincentian community worker, activist and poet Nelcia Robinson, Canadian volunteer Heather Stewart, and local teacher Jillian DeFrietas – as we developed the Glebe Hill Preschool on the outskirts of Barrouallie. Heather and I were Crossroads International volunteers.

{Vincentian community worker and guiding activist behind the Glebe Hill Preschool, Nelcia Robinson. Student Kenisha Patrick, who I would stay with on my return, is to the immediate right of Nel. 1986}

In addition to the preschool, Heather and I volunteered in the capital of Kingstown with the NGO Project Promotions (helping edit their social issues magazine). I also taught photography skills to a group of young men in the community of Layou forming a wedding photo co-operative.

I arrived with – in addition to traveller’s cheques, a plane ticket I kept hidden with my passport in an unused pot, and two pairs of Converse sneakers – a camera, one lens, 5 rolls of black & white Tri-X film, and 2 rolls of colour Kodachrome slide film.

I left St. Vincent with experiences too expansive to fully convey in words, but here’s a start, a humid kaleidoscope of:

* cute kids * rum soaked dominoes * curried goat roti * minivans packed with 25 people * difficulty collecting dues so we could pay the local teachers * dancing in the streets during carnival * a bout of dengue fever * roasted breadfruit * a rooster that crowed hours before sunrise * the shadow of the Grenadian Revolution * discomfort with the intense religiosity * the view from the top of Soufriere volcano * several hundred instant crushes * one bruised heart * the way tropical rain sounded when it hit the corrugated tin roof * and a well-read, curled copy of Small is Beautiful.

Returning to Canada, I developed the film and soon thereafter switched my half-finished university degree from Theatre to International Development. (What is the purpose of art, I thought, as an idealistic young person is wont to do, when there is poverty out there – even though it was political and social theatre that helped set me on the path.)

I volunteered at home with international development organizations, environment coalitions, and an Indigenous Peoples’ solidarity group. I had a short working stint with Unicef Nova Scotia, and a slightly longer time with the Lester Pearson Institute at Dalhousie University, coordinating a public global issues education program. I went back to university and studied Adult Education. Then came another overseas posting in Thailand with Cuso International (known still by many as CUSO or Canadian University Services Overseas).

My time in Thailand was a shorter posting than St. Vincent and admittedly more nebulous. I was there supporting a Nova Scotia-Thailand solidarity project. We created global issues education materials for Canadian audiences, and also sent several Thai farmers to visit successful organic farms in other parts of Asia.

On my return, I would go on to work for Cuso for almost two decades; first as a global issues educator, then as a general program officer involved in recruitment of overseas volunteers. Later came various roles in communications, and I ended my last four years there as Head of Communications for the organization. I made friends too numerous to mention here.

I wrote stories, created videos, produced radio docs, edited a national magazine on development, launched a community media story service, developed communications strategies, engaged in public education, and taught communications skills. Along the way I visited Ghana, Cameroon, Vanuatu, Peru, and Jamaica. These countries may be considered poor economically, but they are rich culturally. I witnessed some of the good news we rarely hear about. Microcredit projects, youth entrepreneur centres, women’s political engagement initiatives, judicial reform.

Truth to told, I don’t know how much I accomplished. No false modesty here; it’s a big world and my efforts were micro-drops in the ocean. I do know that some of my stories inspired people to volunteer or switch to ethical investing or buy fair trade products, some fundraising letters I wrote brought in a fair amount of money, and a bunch of non-profit groups learned new communications tactics & tools from me.

{Me in Sanergo, Ghana, while making a radio documentary on microcredit, looking like a cardboard cutout stuck in front of some rightfully wary women.}

This pales in contrast to the efforts of so many incredible folks I met working at the grassroots of change in the Third World/Global South/Developing World/Majority World (no one has landed on the perfect term yet). I’m not a moral relativist though… I saw some awful stuff too.

Volunteering is no panacea to poverty. It needs to be strategic. We need to know exactly why volunteering is the best form of development for a particular problem — there can be better solutions. No one should think they are individually going to change the world — or a community. Ask the hard question: who are you really doing this for? The truthful answer might still be ok. Done well, volunteering can have a positive impact on you and the people around you.

A few years before I left Cuso, I created a series of ‘This is…’ posters used in recruitment. ‘This is Social Networking,’ with a photo of volunteers together with members of a women’s group. ‘This is Potential’, with a photo of young girls in a classroom.

And ‘This is Not Charity,’ with a photo of a volunteer in conversation with a Cameroonian business advisor. I remember a member of the NGO’s fundraising team not liking that one at all. ‘If we say it’s not charity,’ she said, ‘how do we raise the money?’ Fair enough, that was her job. But this is about levelling a tilted soccer pitch. It’s about investment, in people, in communities, in environmental health. Not in a naïve sense, but a cautiously optimistic way.

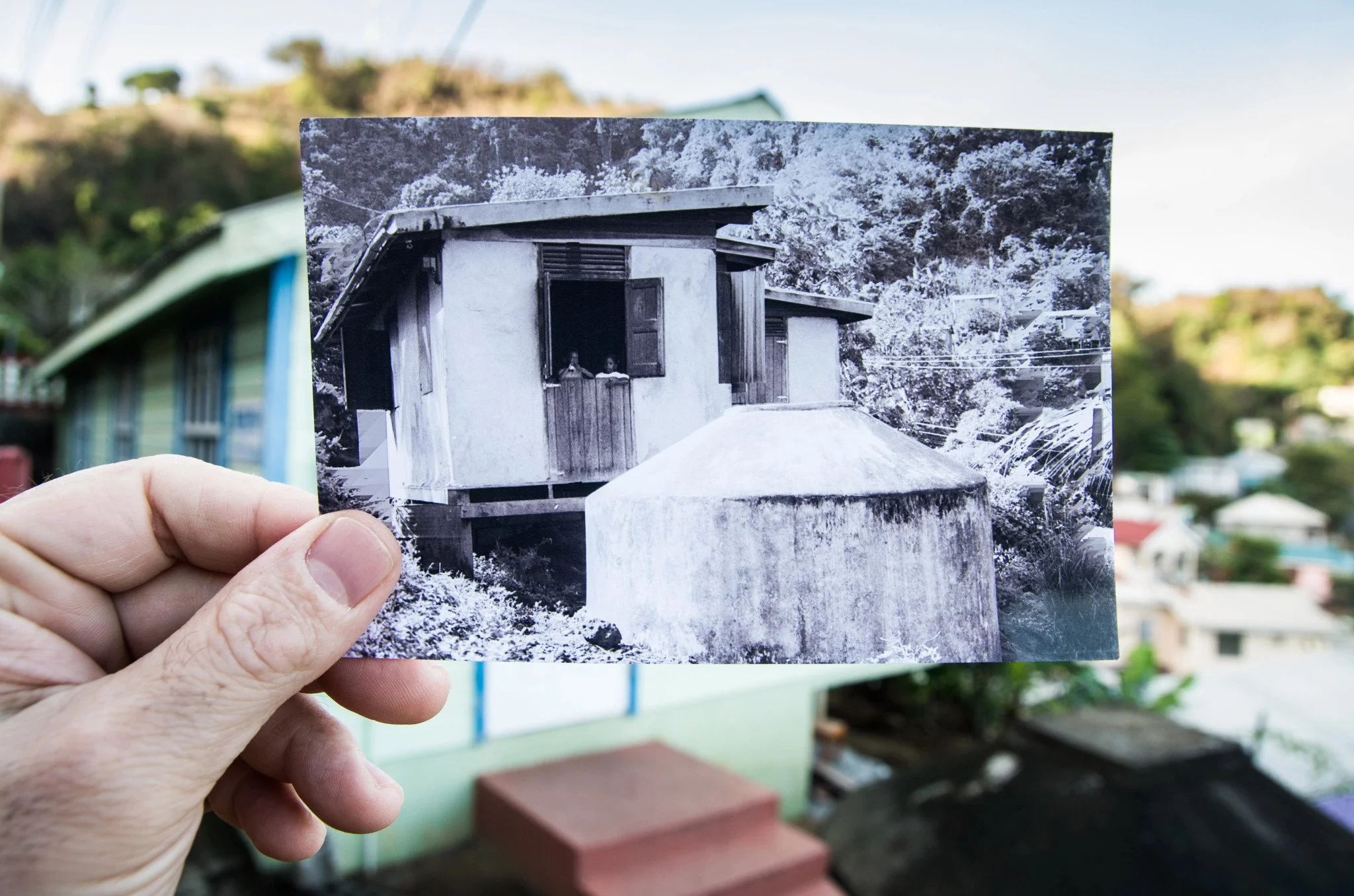

Just over thirty years after my stint in St. Vincent, and after I had left the world of international development for climate work, I returned to Barrouallie with my then 15-year-old son, dragging with us a huge hockey bag filled with books, toys and games for the preschool. Glebe Hill Preschool is still going with teachers deeply committed to the kids; they know what the school can do.

The community has sprawled and compacted, the homes are nicer, the roads are in better shape. Both the village and I were older, and my camera was now digital. Yet Barrouallie smelled the same. The heat felt the same. The plantain chips at snack shops tasted the same. I still got trounced at dominoes.

I sometimes felt the presence of my younger self, like seeing the ghost image in a rangefinder camera. The occasional person did remember me, calling out ‘hey teacha, welcome back’, sprinkled with the affectionate ‘you be balder and bigger now.’ No argument here.

A few offered me Hairoun beer, so no complaints either.

I got to reconnect with Nelcia, the founder of the preschool and still a busy community activist working with women in Vincy and also Trinidad. We stayed with the family of Kenisha Patrick, a student then, and a friend now. She’s an entrepreneur and computer software teacher at the Barrouallie vocational school.

{Kenisha, a student I taught at the preschool way back when.}

I met with some adults who I had taught as kids, some parents who had kids in the school that now live abroad, and some kids of kids. A few even said that the Canadian teachers living in their small town encouraged them to broaden their sights – one of my favourite students (I know we’re not allowed to have favourites) from back then is now a doctor.

I’m wary of volunteers from the ‘North’ romanticizing communities in the ‘South’ (probably because I’ve done it – there’s the good, the bad and the beautiful everywhere), of getting lost in the different, of over-estimating your impact, of not understanding the depth of history.

But it was good to be back. It was good to crowd into a minivan. It was good to hike in rainforest with my son.

And it was very good to eat Vincentian peleau and drink Sunset rum.

– SK